The French Evolution: How France’s evolving basketball culture is shaping the NBA

Nearly 150 years after the creation of the Statue of Liberty, Paris is still sending its tallest defenders to the United States

With the FIBA World Cup right around the corner, many basketball fans are turning to the international scene to find their daily dose of hoops. No continent has drawn more eyes from around the world than Europe, which boasts 11 of the top 15 teams in the tournament, according to oddsmakers. But the continent’s basketball prowess extends beyond international play — Frenchman Victor Wembanyama, the most coveted European prospect in the sport’s history, went first overall in this summer’s NBA draft.

Though Wemby’s origin certainly stands out amongst the Association’s greatest prospects ever, most of whom are American-born, he is just the latest European to make NBA headlines in recent years: Nikola Jokić is the reigning NBA Finals MVP, Giannis Antetokounmpo was two years prior and Luka Dončić has been widely regarded as one of the league’s best players over the last few seasons. The aforementioned players’ achievements represent a larger trend going back to the turn of the century, with players from across the Atlantic becoming increasingly prevalent throughout the NBA. In the 1999-2000 season, there were 20 European players in the league; today, that number has climbed to 53.

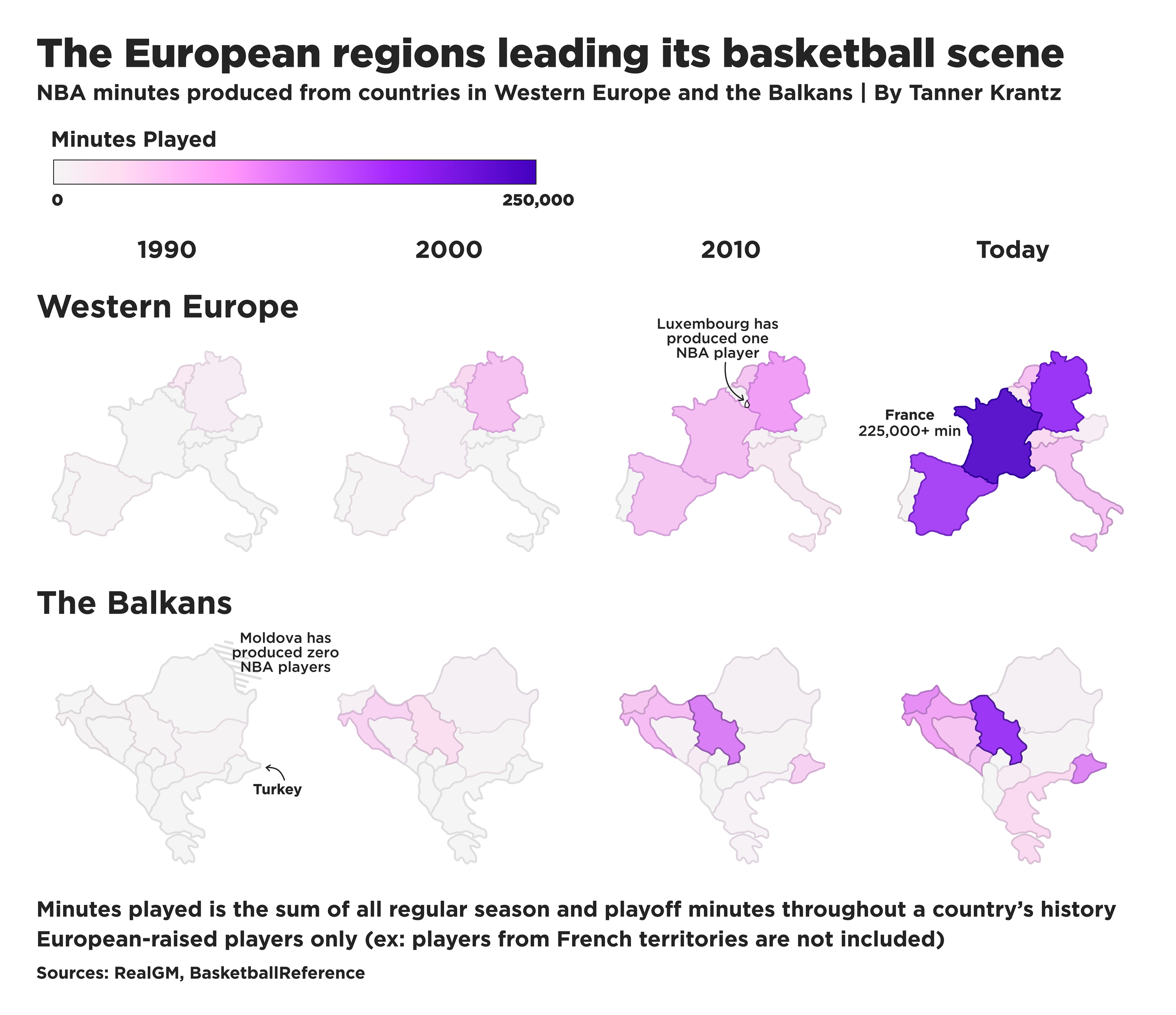

Of course, basketball talent is not evenly spread throughout Europe, with the majority of the continent’s NBA players (sorry, Lithuania) found in western Europe or the Balkan peninsula. The two regions have combined for a total of 14 NBA MVPs, Finals MVPs and Defensive Players of the Year this century. Western European players like Dirk Nowitzki, Tony Parker and the Gasol brothers thrived in the mid-2000s, with one of the four winning the championship six of nine seasons from 2003 to 2011. The Balkan dominance is more recent. Although players like Dražen Petrović and Peja Stojaković were undoubtedly great in the 1990s and early 2000s, they were merely trailblazers for the myriad of Balkans who would follow; there have been at least two Balkan-raised players on each of the last five All-NBA First Teams.

Yet no country reflects European basketball growth like France, which started the century having developed just one NBA player and now finds itself behind only Canada as the international country with the most NBA players all-time. In the last two years alone, eight French players have been drafted, three of whom were lottery picks, including Wembanyama. His new team, the San Antonio Spurs, have already been monumental in showcasing France’s basketball talent. The first two Frenchmen to have storied careers in the NBA – Tony Parker and Boris Diaw – spent more time with San Antonio than any other team throughout their long careers. Ironically, Wembanyama’s most recent pre-draft teams, ASVEL and Metropolitans 92, have been owned and run by Parker and Diaw, respectively. Now Wemby and his fellow rookie teammate, Sidy Cissoko, look to build a similar legacy as French players – specifically, Parisians – in the Alamo City.

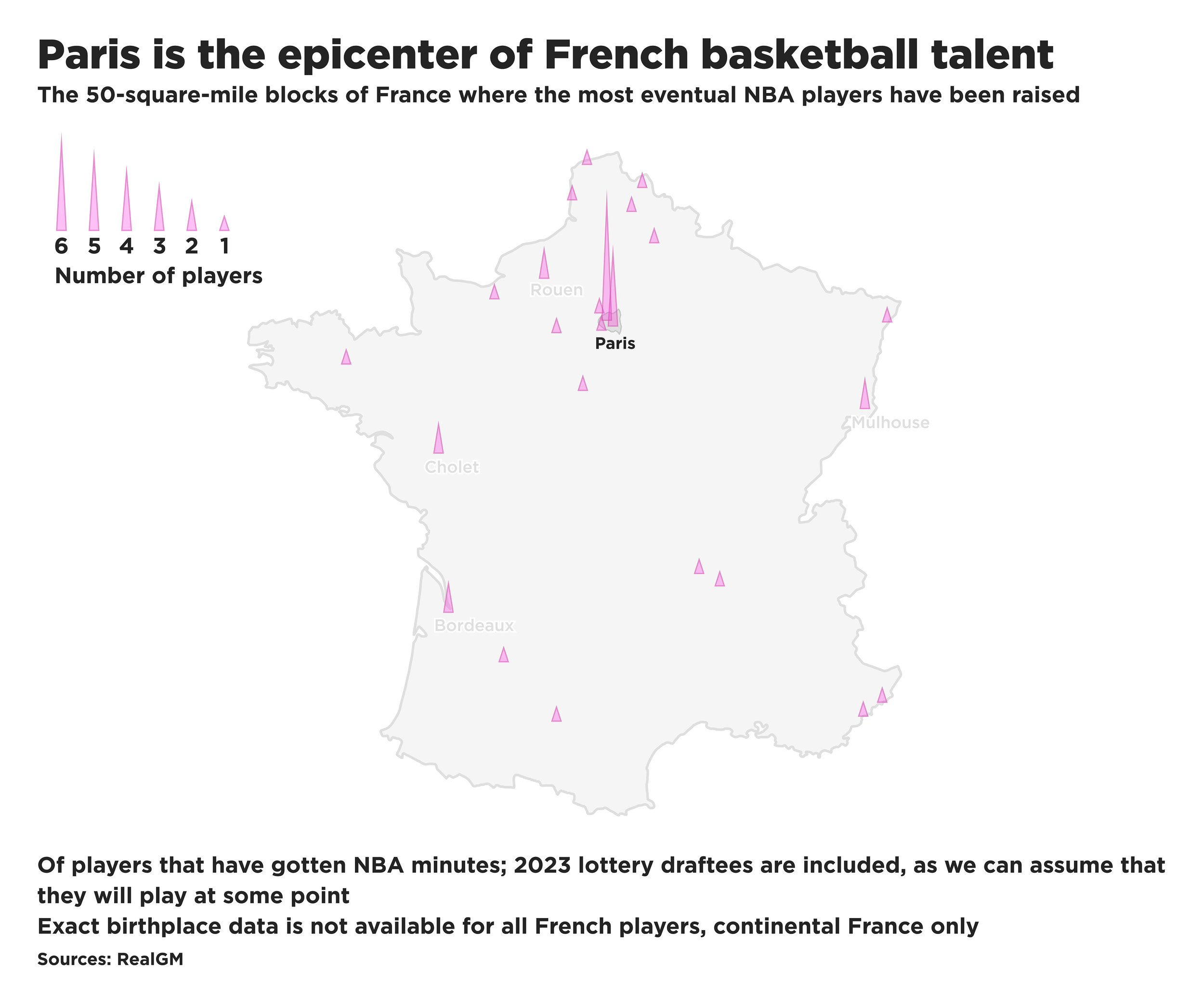

Just like the Spurs before them, the newly-drafted pair grew up in the suburbs of Paris, host city of the NBA’s latest international game. Wembanyama is from Le Chesney, a commune west of Paris, while Cissoko grew up in Saint-Maurice, just east of the capital. Bilal Coulibaly, Wembanyama’s Mets 92 teammate and the seventh pick in last month’s draft, was also raised on the outskirts of Paris in the commune of Courbevoie. They are only a few of the many Parisian players throughout the NBA, as the city is home to well over a third of all Frenchmen to have played in the league, including – of course – Parker and Diaw. And just as Fashion Week brought NBA players to Paris a few weeks ago, the city is becoming increasingly fashionable to front offices, as well; of the 12 French players drafted since 2019, 10 grew up playing in the nation’s capital.

On the surface, this makes sense: Paris is France’s largest city, boasting about a sixth of the country’s total population. However, that does not explain why it is an NBA hub while other major European cities like London, Berlin and Madrid are not.

Lindsay Sarah Krasnoff, the author of Basketball Empire: France and the Making of a Global NBA and WNBA, says the answer does not lie with Paris itself, but rather with the basketball development systems across France: “It is country-wide that the professional club youth academies or federal youth development centers develop and train such players.” As the fulcrum of France’s population, Paris naturally houses many basketball institutions and eventual professional players. But it is not merely quantity that has allowed Paris to dominate the French basketball scene, as the city’s most notable training ground, INSEP (or France’s national sports school), has developed 16 NBA players alone. The group includes three NBA champions in Parker, Diaw and Ronny Turiaf, current New York Knick Evan Fournier and even the Swiss-born Clint Capela. State-backed schools like INSEP and professional club youth academies (such as Nanterre, Wembanyama’s formative club) have fostered skill development while allowing prospects to gain professional experience, a recipe that has proven to be successful since Parker entered the league in 2001.

Along with youth development systems, Krasnoff mentioned France's cosmopolitan nature as to why it produces more NBA players than its European counterparts, which she described as “a reflection of France's complicated, complex colonial past.” In the latter half of the 20th century, France welcomed millions of immigrants from its numerous colonies throughout Africa and the Caribbean, 38% of whom settled in Paris. One of those settlers was Wembanyama’s father, Felix, who grew up in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. That is a consistent story amongst the NBA’s Frenchmen; players like Diaw, Nic Batum and Ian Mahinmi were all born to at least one parent of African descent.

In hindsight, it is only fitting that the first basketball game outside of North America was played in Paris. The 1893 game happened on the world’s oldest basketball court, a Parisian Y.M.C.A. outpost. But it would not be until nearly 100 years later that the sport would truly catch wind in France, when the “Dream Team” traveled to Europe for the 1992 Olympic Games in Barcelona. As “The Greatest Team Ever Assembled” took the world by storm, French viewers were captivated by the culture surrounding the NBA, from sneakers to fashion to music. Only a few years later, the Michael Jordan-led Chicago Bulls went to Paris for a preseason game, a trip that has since been immortalized with the release of ESPN’s 2020 documentary The Last Dance.

That excitement around the NBA has made the league a dream for many French children, and a thriving development system has made that dream a reality for more and more players each year. In the 21st century, France (specifically Paris) has re-established itself as the center of global basketball, and the nation is far from done. In late June, France beat the United States for the first time in the FIBA U19s, and another French prospect, Zaccharie Risacher, looks to follow in the footsteps of Wembanyama and Coulibaly as a top-10 pick next season.

Wembanyama, Coulibaly, Risacher and the rest of France’s emerging basketball talent now hope to leave their own mark on the sport, just as Parker, Diaw, Batum, Rudy Gobert and many others have before them. But before they can do that, France has a chance to stamp their basketball legacy with gold at the 2023 FIBA World Cup, where I know that Knicks fans from all over the world will be rooting for Les Blues’ Frank Ntilikina.