How to draft with data: Should mid-first round teams like the Knicks draft polished or raw prospects?

Every draft cycle, outside of the top 10 there are always players considered “polished” and “safe” compared to those considered “raw” and “risks to bust.” But via discoveries through data, could drafting a raw player actually be the safer bet by the numbers?

Drafting for upside vs. drafting for Day 1 production is one of the most common narratives in sports media. Wherever one looks for prospect coverage, they find talking heads slapping the same archetypal tags like “NBA-ready,” “raw,” or “a project” on players. The binary nature of these labels are a bit of an oversimplification, but at their core they pose an interesting question: Is it better to select polished, lower ceiling players, or higher ceiling prospects who will struggle early in their careers?

Today, I’m only going to dive into prospects picked in the mid-late first round range (picks 13-30), because as of writing, that seems like where the Knicks will select in the draft (they have the 19th, 21st, and 32nd pick, and may consolidate picks to move up to the earlier teens). There’s a number of intriguing options in the class that are in that range, and fall on either side of this philosophical raw/polished fence: older, likely immediate contributors like Corey Kispert and Davion Mitchell, and also developmental, tools-based prospects like Ziaire Williams and Keon Johnson.

The goal for this article is to look at prospects of the past, check where they fall on the raw vs. polished spectrum, see if we can take away any lessons from that data, and apply it to this year’s draft class.

It’s difficult to identify which prospects were flagged as raw or polished going into their draft year; there’s no individual metric or stat to measure it. To combat this, I’ll try a few different methods to isolate these prospects, and see what we can conclude.

But first, a threshold question before we take a look at drafts of Christmas past: How does one define a raw prospect and a polished prospect? While the meanings of raw and polished can sometimes be undefined, for the most part, people know what you mean when you use these terms in casual draft conversations — raw prospects are usually behind their counterparts in the skills department, but carry some sort of unique physical gift that, if nurtured correctly, could allow them to be an impact player. Polished players are usually older, and while they don’t have the same athleticism as the raw prospects, they are more refined technically, and probably have an NBA-ready skill — like spot-up shooting or on-ball defense — that allows them to play in a rotation as a rookie.

Now that that’s out of the way, let’s begin with the first method: the Barttorvik test.

Barttorvik method

Barttovik.com is a site that allows you to filter every college player in the nation through a number of statistical and situational thresholds. The idea for this piece was born through messing around on Barttorvik, trying to find prospects with interesting or unusual skill sets. I set out to create a series of filters to isolate raw or polished prospects, and after many iterations, came up with this:

Raw - TS% below 56%, more than 2.5 fouls/40, more than 20 dunk attempts, drafted as a freshman or sophomore, drafted between picks 13-30

Polished - TS% above 56%, less than 2.5 fouls/40, less than 20 dunk attempts, drafted as a sophomore, junior or senior, drafted between picks 13-30

(All stats are taken from the prospects’ draft year, and pure centers were excluded, as the path to 20 dunk attempts is too easy for them.)

These stats may seem arbitrary, but they all serve a purpose: the TS% is to separate refined scorers from the under-baked chuckers, the fouls are to identify experience and polish on defense, and the dunk attempts are to determine athleticism (despite how inconsequential dunking skill is, dunking volume is usually a good indicator of functional athleticism). All of these factors should, in theory, create two solid buckets to catch raw and polished prospects, respectively.

(For those who are curious, in this upcoming class the filter spits out Corey Kispert, Ayo Dosumnu, Chris Duarte, Davion Mitchell, and Franz Wagner as polished, while Scottie Barnes, Keon Johnson, Greg Brown III, and JT Thor come out as raw).

After running the 2011-2015 draft classes through the filter, we get this list:

Polished players

Cam Payne (No. 14 pick, 2015)

Shane Larkin (No. 18, 2013)

Sam Dekker (No. 18, 2015)

Jerian Grant (No. 19, 2015)

Delon Wright (No. 20, 2015)

Tony Snell (No. 20, 2013)

John Jenkins (No. 23, 2012)

Shabazz Napier (No. 24, 2014)

Reggie Bullock (No. 25, 2013)

Jimmy Butler (No. 30, 2011)

Kyle Anderson (No. 30, 2014)

Raw Players

Zach Lavine (No. 13, 2014)

Moe Harkless (No. 15, 2012)

Kelly Oubre (No. 15, 2015)

James Young (No. 17, 2014)

Terrence Jones (No. 18, 2012)

Tobias Harris (No. 19, 2011)

Rondae Hollis-Jefferson (No. 23, 2015)

Jarrell Martin (No. 25, 2015)

Archie Goodwin (No. 29, 2013)

Kevon Looney (No. 30, 2015)

Royce White also qualified for the raw prospect bucket, but his career was complicated by a court battle over the conditions of his contract, as well as struggles with mental health, so he was excluded from the data.

After gathering these lists, I looked through each prospect and charted their development curves. I’ll get into all of the exact numbers later, but for now I’ll keep it light, with only the main takeaways from the data.

Unsurprisingly, the raw data set featured more busts (players who ended up as back of the rotation guys or worse), while also having several more high-end outcomes (plus starter or better). The polished set had a huge outlier in Jimmy Butler, but apart from that, most of those guys ended up as middling bench players. The results here make sense; rawer prospects should produce a wider range of potential outcomes, so logically they produced more flameouts and stars. Still, the sample size of 22 total prospects is way too small to conclusively answer any questions. We’re going to need more.

*It’s important to note that while the average pick between the two groups of prospects is virtually identical, there were a few more top-20 picks in the raw set than the polished set.

Age

Although not as precise as some of the other methods, age allows us to cast a wider net of prospects, and it should be able to provide a solid baseline of data to make up for the small sample sizes of the other two. The premise here is that most college NBA prospects that go back for their sophomore season (and beyond) don’t prefer to do so, rather they simply aren’t good enough yet to be drafted in a desirable range. They get an extra year(s) to refine their technical skills, and make up for any athletic or bio-mechanical deficiencies they possess in hopes of improving their draft stock. Drafted freshmen, on the other hand, are more likely to be carried by their superior athletic traits in college, allowing them to be drafted even with a relatively raw skillset and sometimes even with less statistical production. Because of this, one-and-done prospects are usually rawer, while older prospects are generally more refined. While this idea obviously isn’t consistent across every example and player, the correlation between age and rawness should be strong enough to produce a worthwhile data set.

It’s also intuitive that younger players are more raw; they’re quite literally behind the other prospects in their development curves. A 22-year-old has had three more years than a 19-year-old to become good at basketball!

For this section’s data, I flagged prospects with a draft age below 20 as raw, and prospects with a draft age above 22 as polished. This method leaves out players with an age in the middle, but let’s just see where it takes us. The players are taken from the 2008-2013 draft classes, and of course drafted between picks 13-30.

There were over 50 players in this set, so I’m not going to list them all, but after charting the old and young groups of prospects, I realized that there was a large discrepancy between the results here and the other methods employed in this piece. The “old” set had almost no real contributors (George Hill was the best of the bunch), compared to the “young” set containing multiple All-Stars in Jrue Holiday, Kawhi, and Giannis. It was such a massive outlier that I decided to throw this data out.

I still think age is a valuable indicator of how far along a prospect is in their development, but clearly it was too broad to provide anything worth using on its own. This might be common sense, but sometimes it’s worth confirming our intuition!

Mock draft language

Now we’re getting weird.

I searched through two mock drafts or big boards for every draft from 2005-2015, and charted the players from each class who were described with the words “raw” or “project,” and the ones described as “NBA-ready” or “polished.” I stuck to the typical mainstream outlets like ESPN and CBS and as much as I could, but for some of the older drafts I just had to take what I could get.

(The data gathering process went significantly faster once I was introduced to the wonders of Command+F...)

This is no doubt an imperfect method, as at the end of the day, the media aren’t the ones calling the shots in war rooms. Still, it’s a good way to finger the pulse of NBA media at the time of each of these drafts. And while the ever-present groupthink of sports media can be tiring, it’s still useful for pointing out obvious narratives and opinions of the past that might not be remembered. After all, none of us earthly mortals have the capacity to remember if Memphis legend Stromile Swift was considered a project pick or not.

Just like the age section, the list here is way too long to write out in full. The raw prospects were highlighted by Jrue Holiday, Rudy Gobert, and some skinny Greek kid, while the polished set featured... Roy Hibbert.

Some other notables from each set:

Polished - Bogdan Bogdanovic, Aaron Afflalo, and both Morris brothers

Raw - Nic Batum, Jeff Teague, and Clint Capela

After tallying up the data, the mock drafts had virtually identical numbers as the Barttorvik section. There were several more stars coming from the raw set than the polished set, and the polished prospects generally stuck around in the league more often than the raw guys. Now that we’ve got all our data, it’s time for some graphs!

The data

I know graphs are usually a lot to look at, so instead of bombarding you with lines and dots lacking context, I’ve only included the main few charts that drive the thesis of the article home, along with some quick takeaways from the graphs. Hopefully that makes this section a little more digestible and pleasant to read.

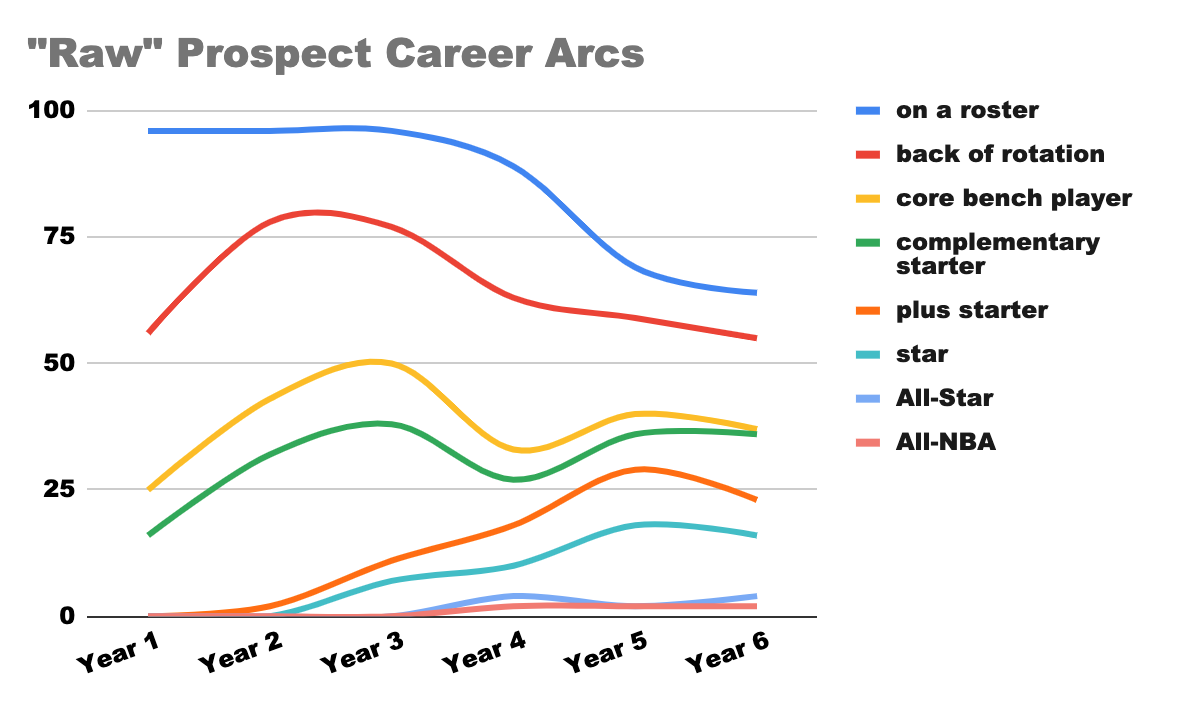

The first graphs show the career arc up to Year 6 for both sets of players. The X axis here is a % of all prospects from this evaluation pool, so for example, over time less and less of them will be categorized as “on a roster’’ as some prospects flame out of the league, and over time more will be plus starters and All-Stars as guys come into their prime.

Lastly, all of the benchmarks used in the graph include players that also met higher benchmarks. For example, Giannis still contributes to the lines for “on a roster,” “back of rotation,” etc., all the way through All-NBA, since he has been each of these things.

Some of the descriptors I used, like “core bench player” and “plus starter”, are admittedly hazy in definition, as they don’t rely on concrete benchmarks like “on a roster” or “All-Star.” However, I thought they were necessary for sorting out the prospects, and if I had just sorted them by bench player/starter/all-star, the results wouldn’t have been quite as precise. Still, I think it’s fair to take some of the more subjective groupings with a grain of salt.

Above, I have also included a more simplified graph here that doesn't provide the context of year-to-year progression, but gives a clearer view of the possible outcomes for each set. In all, 50 players were isolated and charted in the data.

So what can we learn from these attempts to isolate raw and polished prospects from recent drafts taken from 13th to 30th?

Data takeaways

Only 26% of the polished prospects I looked at were out of the league by Year 6 of their careers, compared to 36% of the raw prospects. This confirms my assumption that the raw players would flame out more than the polished guys.

On the other hand, 23% of the raw prospects became plus starters, while only 13% of the polished prospects did the same, confirming that the raw prospects eventually blossomed into impact players more often than the polished prospects.

There were more polished prospects who played in a rotation as a rookie, but not by as much as you might think: 64% of polished prospects played in a rotation as a rookie, versus 56% of raw prospects. (I defined playing in a rotation as getting 12-plus minutes per game and appearing in over 50% of regular season games). However, I think this gap might be skewed by the fact that win-now teams are more likely to draft these polished prospects, meaning the polished set had harder rotations to crack, on average. Additionally, the rawer prospects were probably given longer leashes and allowed to make more mistakes, as they’re expected to be rough around the edges early in their careers.

I wouldn’t put too much stock into the polished set having slightly more All-Stars and All-NBA appearances than the raw set, as each only had a few anyway, so a one or two player difference is too small of a discrepancy to warrant sounding the alarms. Stars are rare outcomes for both polished and raw prospects in the 13-30 range.

My main takeaway is drafting rawer players in this 13-30 range lands significantly more difference-makers than safer picks.

Final thoughts

After delving through the data, it’s clear that historically, swinging for upside has worked out more often than settling for a “safe” pick in the mid-late first round. Unless a team is a championship contender, and there is a true Day 1 positive contributor on the board in this area of the draft (very rare, read: Chris Duarte this year, or Desmond Bane last year), it’s beneficial to accept the relatively small risk that comes with drafting a project. And if we reframe what “risk” truly means in this context, is it even risky at all?

Going off of the traditional definition of bust for a non-lottery pick (a player falling out of the league), yes, the raw prospects busted more often than the polished ones. But the players in the “meh” bucket of the second graph still returned below-average value for their draft slots. Typical back-of-rotation NBA players provide minimal value, while non-NBA players provide none. Is that distinction large enough to warrant not being considered busts? If not, then the polished set actually has slightly less busts, while also containing much more high-end talent.

Not only is the data clearly in favor of drafting rawer prospects outside the lotto, but the league is starting to widen this gap even more with its recent movement towards valuing off-ball players. The NBA has mostly gotten rid of the stigma around projected low-usage/off-ball players being drafted high; De’Andre Hunter and Mikal Bridges were both lotto picks recently, and Corey Kispert is primed to follow them in this draft. As counterintuitive as it may seem, elite role player bets are made in the lottery nowadays. Guys like Hunter and Bridges don’t fall to the teens anymore, and the role player options in this range are no longer premium (with the exception of a Bane or Shamet slipping every year or two). Because of this, the argument to “go get a Day 1 contributor” (i.e., a polished prospect) doesn’t hold the same weight it once did. Now, you have to squint to find prospects outside the lotto who project to be above replacement level in the first few years of their career. The value of instant impact rookies to contenders is virtually extinct, simply because all the good ones are usually picked early nowadays. They need a massive red flag (again, Duarte or Bane being relatively ancient are great examples) to drop out of the lotto. And for every Duarte, there are 10 of the usual suspects: three- or four-year college players with one NBA skill, often lacking the ancillary traits necessary to allow them to stay on the floor in the playoffs. Despite this, GMs continue to waste their mid-late picks on mediocre “safe” talent.

And yet… you can’t really blame them for it. A conservative draft bias is always going to exist in every front office in sports — GMs want to win championships, but they also want to keep their jobs. When picking in this mid-late first range, drafting a bust is seen by ownership as a failure, while picking a guy who bounces around the league for seven years is viewed as an acceptable job. The actual difference in on-court value returned from those two hypothetical prospects is minuscule, but the swing in job security between them is much larger. If the Lakers had selected me instead of Moe Wagner back in 2018, something tells me the franchise wouldn’t have fallen to its knees. Front offices would rather take a guy they know will protect their reputation, instead of rolling the dice on a better prospect and risking their paychecks. This disconnect leads to over-drafting of JAGs (just a guy), and players like Aleksej Pokusevski and Kevin Porter Jr. falling all the way to the mid/late first.

That’s not to say that every team should always be looking for a star this late in the draft. For teams who already have cornerstone offensive creators, it can be better to take a safe/low usage player. These teams generally have less creation burden to spare, which can be detrimental to the development of rawer prospects who might need the opportunity to play through mistakes while on ball. And if a franchise is just looking for someone to round out their regular season rotation on the cheap, burning a first rounder on a Grayson Allen is acceptable. But in these instances, you can usually find a better player by just trading the pick anyway.

The sooner we begin to accept draft picks as lottery tickets, the better. Teams need to embrace the randomness and crapshoot nature of the draft, instead of trying to “hit” on every pick by attempting to meet a certain threshold of player that is considered fair value returned for that draft slot. It’s wishful thinking to ask real GMs to adopt this philosophy; they want to avoid getting burnt at all costs, and all future GMs will carry this same bias due to the nature of NBA business. But hopefully Mr. Rose and Co. err on the side of informed recklessness this draft, and truly make the best pick possible, regardless of the personal consequences riding on it.