Julius Randle, reasons for Knicks hope come the playoffs & being like water

This year, Julius Randle can become the playoff hero Knicks fans long for. All he needs is more balance. And less.

In an offseason in which he spent more time than he would’ve liked recovering from ankle surgery, unable to play basketball, Julius Randle had time to think. To study. To reflect. One of the teachers he turned to: Bruce Lee. One of Lee’s lessons: be like water.

Balance is necessary in order to survive the 24/7 post-capitalist hellscape, but survival is a tourniquet. To truly thrive and feel alive, equilibrium doesn’t cut it. It’s about being your fullest, bestest self, while also being capable of balance when required. Randle’s play so far this season is toeing the line between being balanced and being water. And in that truth lies the hope that his third trip to the playoffs will be the charm.

There are parallels in Randle’s regular season and playoff shot charts. This year his on-court plus/minus is a career-high; his on-off plus/minus is tied for his best ever. This coincides with his shot profile being more imbalanced than it has been in years. Even with some similarities between 2021, his first great year as a Knick, and this season, the changes are what’s most striking.

71% of Randle’s shots in 2021 were 2-pointers; this year, 72% are. But over time, there’s less balance between what kinds of twos he’s taking; the range grows larger every year. In ‘21, 16% of his twos came from 0-3 feet, 18% from 3-10, 20% from 10-16 and 17% from 16 to the arc. That’s remarkable balance; the range between the least- and most-commonly used area is only four.

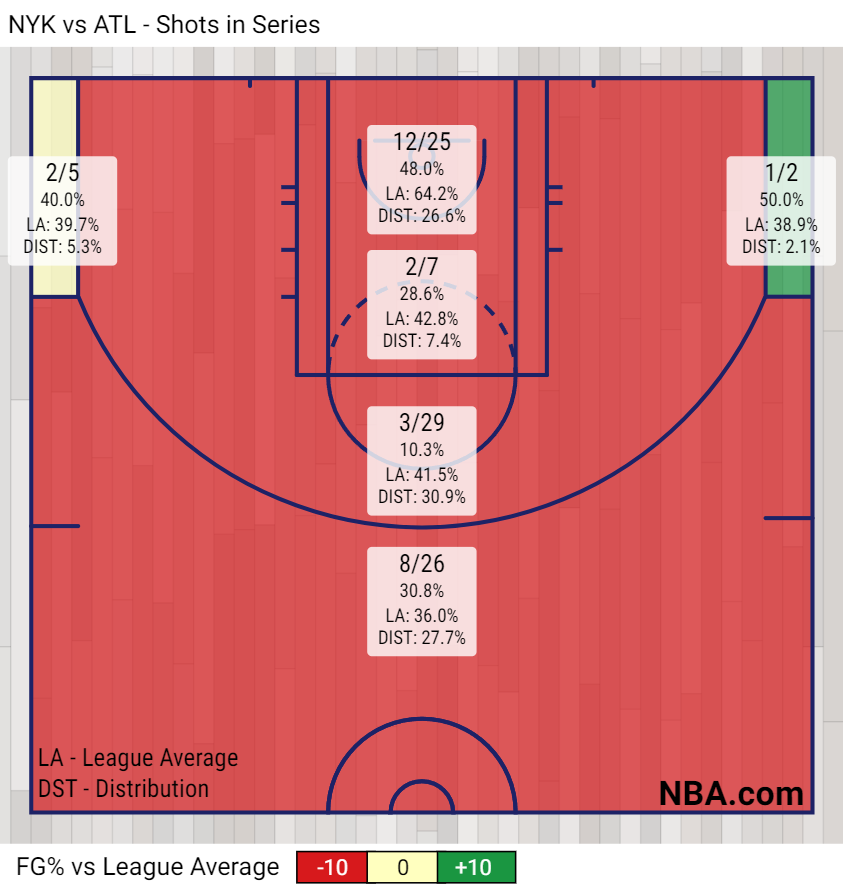

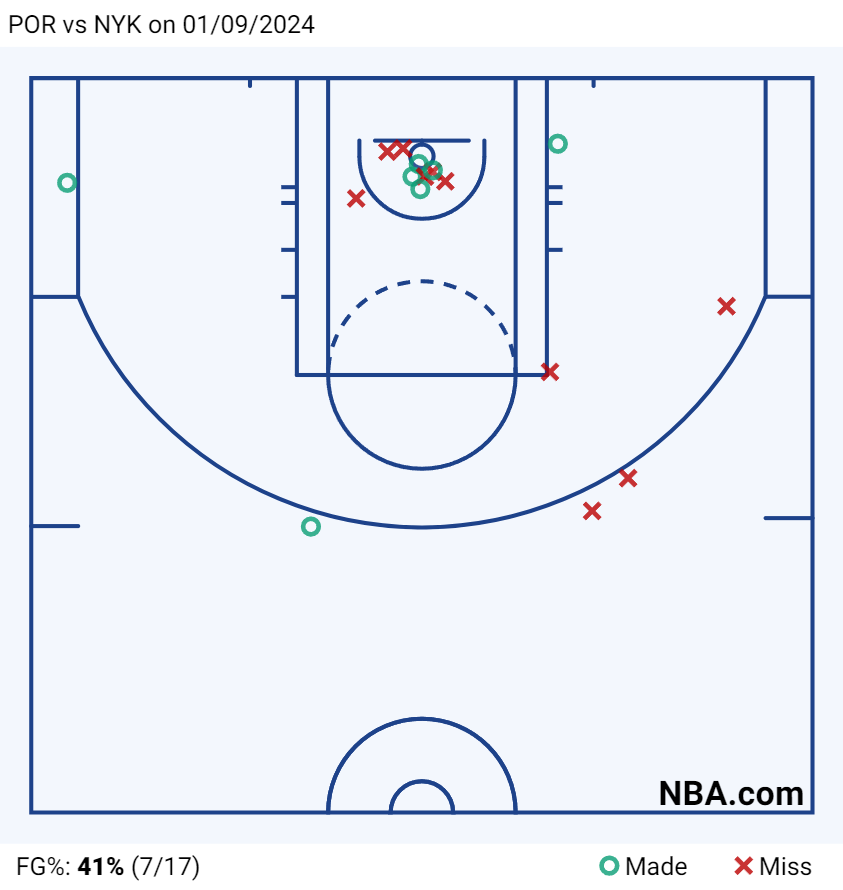

2021 Randle was equally balanced in his regular-season accuracies. From 3-10 feet, he made 41% of his looks; from 10-16, 43%, and from both 16 feet to the arc and beyond, 41%. All the statistics from the Atlanta series are a paint-by-numbers fiasco, but one of the more salient is Randle’s shot chart.

It’s not a perfect comparison because the NBA.com playoff shot charts break up the 2-point world into three areas, whereas the numbers I cited before, courtesy of basketball-reference.com, splits it in four. But the two biggest points in those numbers still pop: Randle making only three of 29 shots in the long midrange and taking nearly a third of his twos within a few feet of the rim, twice as many as he had during the 2021 season.

That may seem like a lotta syllables to tell you what your eyes made clear two and a half years ago: that the Hawks series was hell for Julius. But as the Koran teaches, “A time will come when no one will be left in Hell; winds will blow and the windows and doors of Hell will make a rattling noise.” From the lowest of depths, Randle began to rise.

While 2023 saw him attempt a career-high 44% of his shots from deep – despite a sub-par 34% marksmanship – dig into Randle’s shot profile and there are signs of intelligently designed efficiency. Randle’s 3-point attempts were up 14% last year; his shots at the rim were up 6%. Where did that 20% come out of? The two longest midrange zones, that’s where. He took fewer shots from the least efficient areas while taking and making a higher percentage from 0-3 and 3-10 feet. If you remember 2021 Randle, he was a midrange maestro, hitting baseline turnarounds left and right. I’m not sure he made a single one last year. Remember how in ‘21 his midrange “range” was only four? Last year it was 16. This season it’s 26 (30% of his midrange shots are from 3-10 feet, versus only 4% from 16 feet to the arc).

2023 then saw a late-season ankle injury and a hurried return for the Cleveland series. Then came the late-series ankle injury, which kept him out of the Miami opener and affected Randle the rest of the way, leading to surgery, Bruce Lee, and water. Are there patterns worth noting from his playoff shot charts last season? There are. How meaningful they are to the 2024 Knicks and beyond is hard to say, given that 2023 Playoff Randle is not a Randle they hope to see again, i.e. injury-hit.

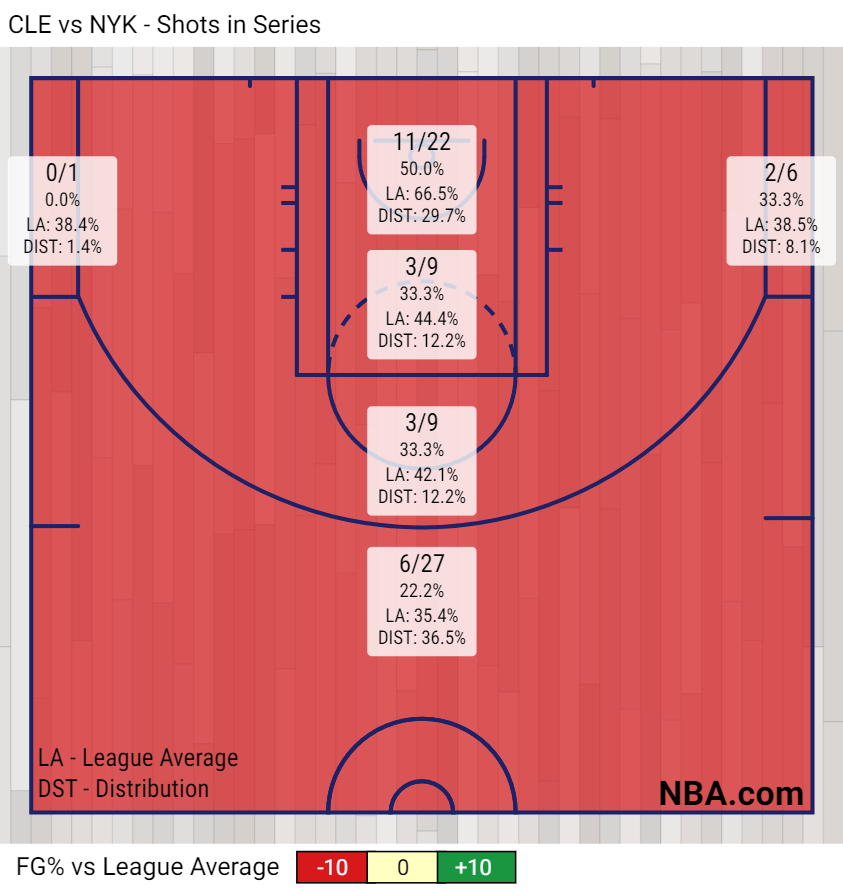

Compare his shot chart from the Cleveland series to the Atlanta series and you see Randle again taking 30% of his shots at or near the rim, an increase from his 22% regular-season rate during the season, echoing what we saw in 2021.

Interestingly, Randle took 20 fewer shots in a series his team won than he did when they lost in ‘21. Most of that is chalk-uppable to Jalen Brunson’s presence. But it’s noteworthy where Randle cut down the most: after taking six shots a game from the two longer midrange zones against Atlanta, he took just two a game from the same area against Cleveland. Randle struggled to finish his close-up looks, perhaps understandable playing on a bad ankle against Jarrett Allen and Evan Mobley.

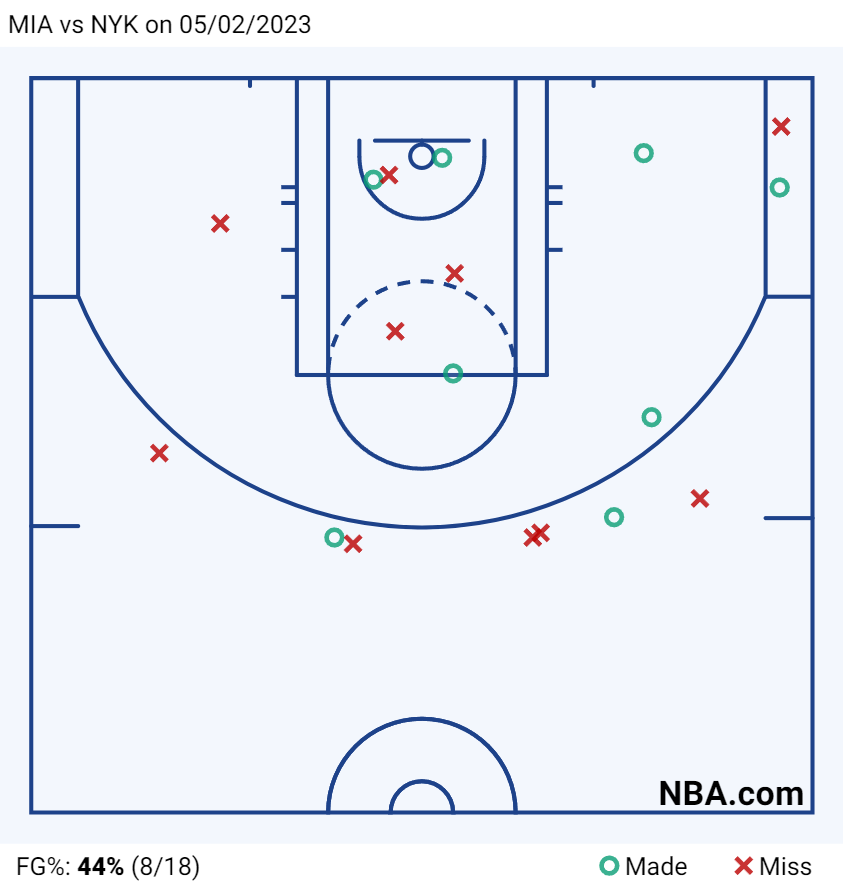

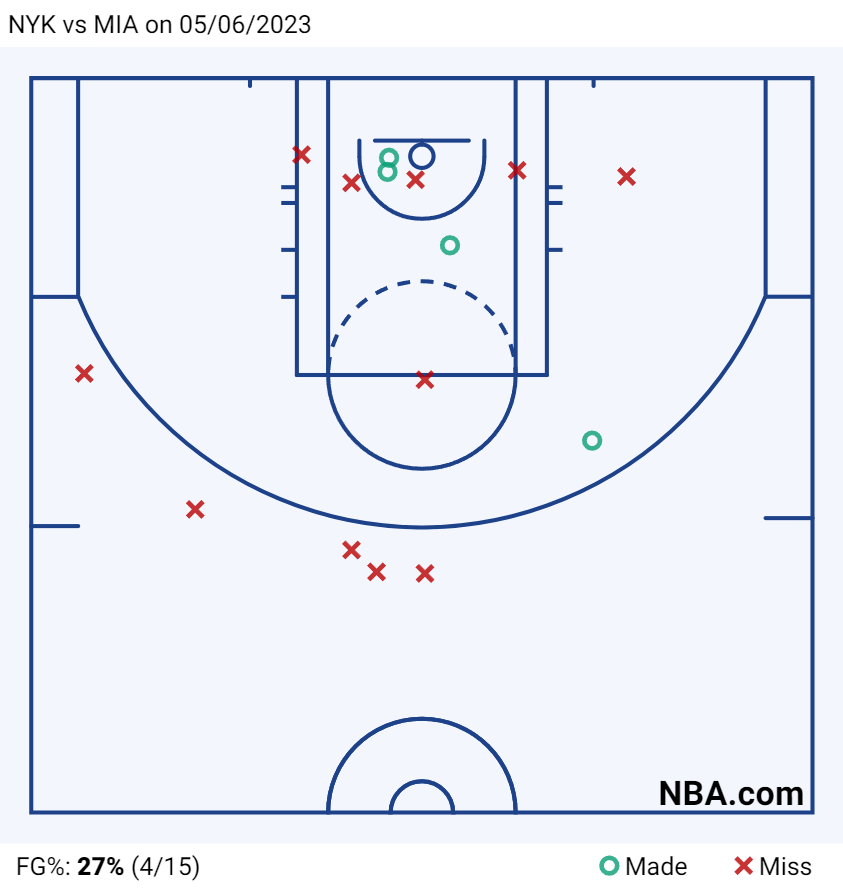

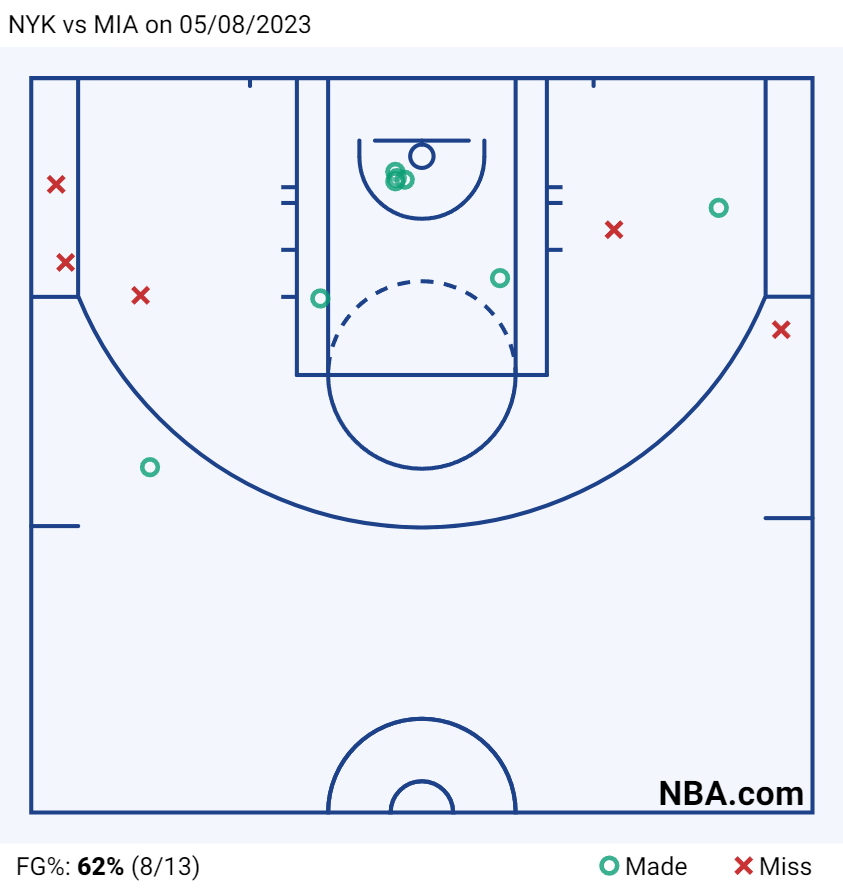

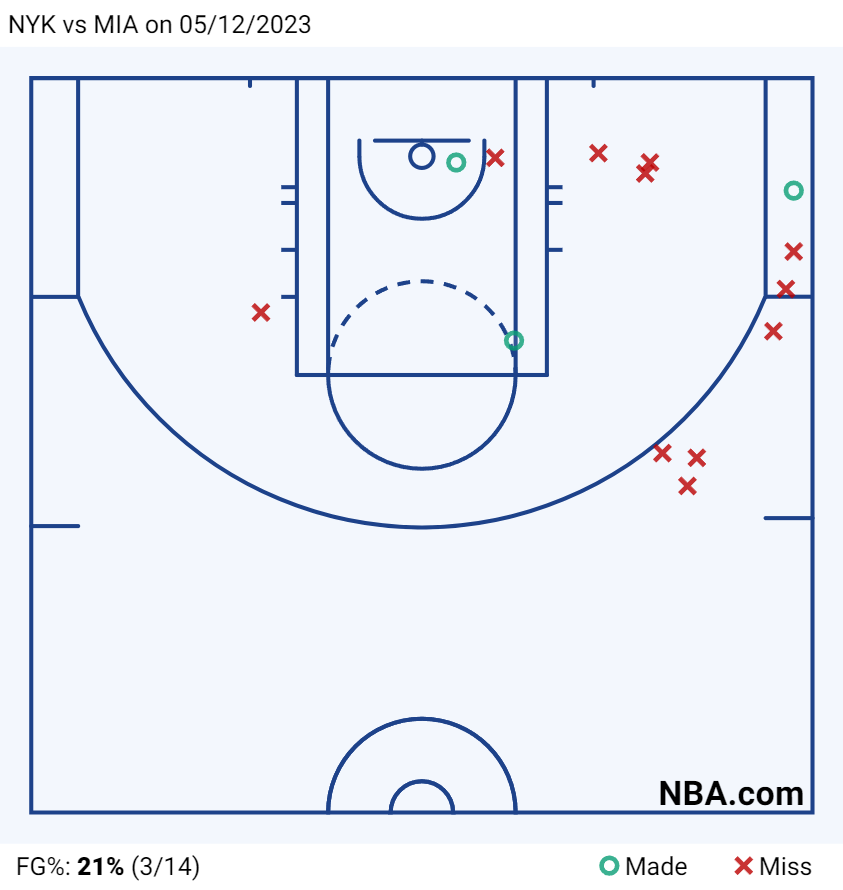

I couldn’t find one series-encompassing shot chart for Randle against Miami, so I’ll share his charts from Games 2 through 6, the games he played that series. Again, some interesting patterns emerge, even in this limited data.

When Randle returned against the Heat, he was far more efficient down low, making 11 of 14 shots from that area and 6 of 14 from 3-10 feet. The low number of attempts from these areas jumps out; again, I’ll assume that had something to do with him returning from a second ankle injury and being welcomed back by a lot of Bam Adebayo defending. Process-wise, Randle took fewer of the types of shots he probably shouldn’t, and made a good percentage of the ones he probably should.

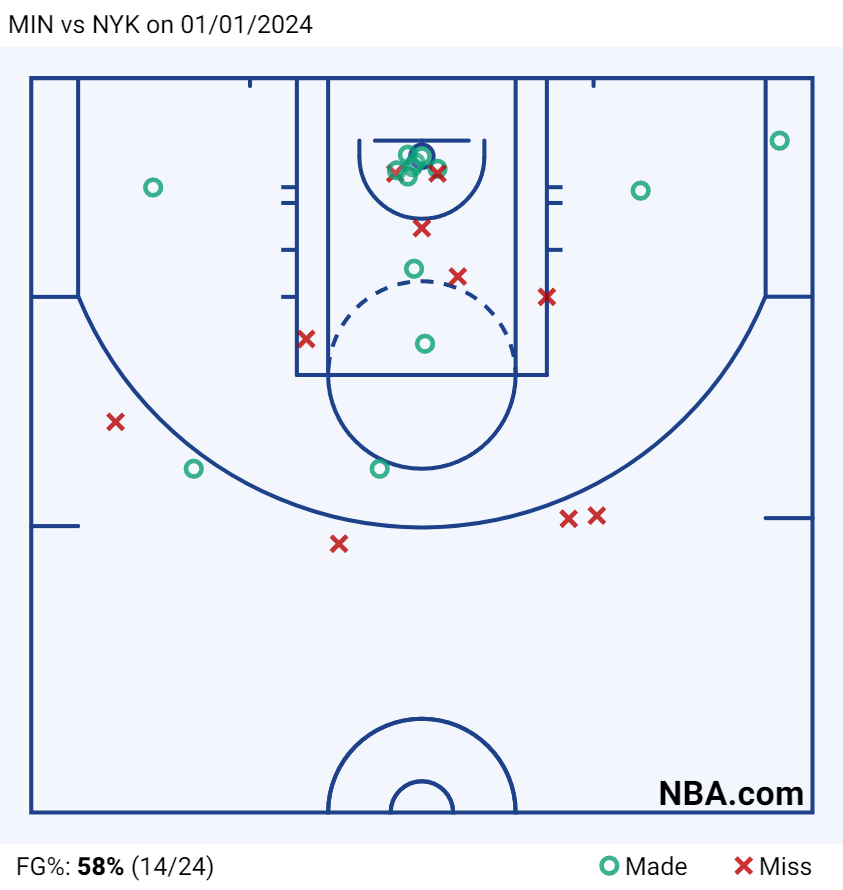

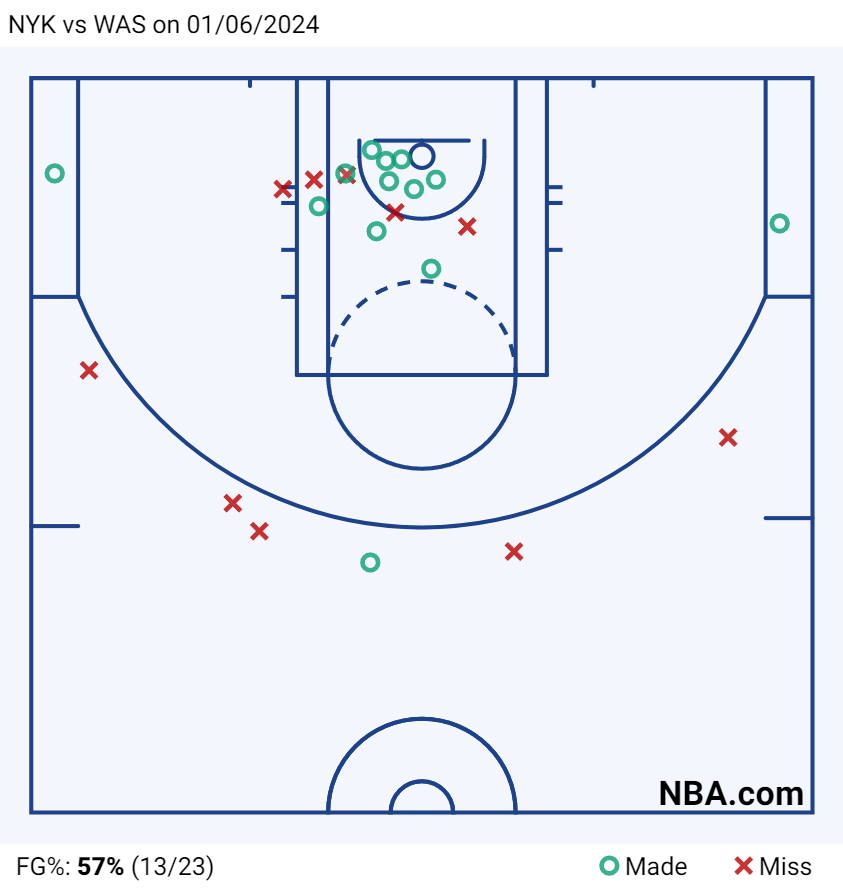

Also I have no idea if this means anything, but it’s interesting to note that in the three games Randle played well against the Heat – Games 2, 4 and 5 – there’s symmetry in his shot charts. He’s working both sides of the floor. In the games he struggled, he sticks mostly to one side. Coincidentally or not, here are Randle’s five shot charts since the OG trade. Symmetry abounds.

If you take in Randle’s three playoff series with a zoom-out lens, you can see signs of better process and (gradually) improving results. Do three fair games out of five against Miami point to better days ahead? Neither Randle nor the Knicks are where they want to be, not yet. That comes with time, which takes time. Public service announcement: it’s that way for everybody, Patrick Ewing wasn’t “Patrick Ewing” in a postseason until his fourth and fifth series, the 1990 playoffs against Boston and Detroit.

After the Washington win, Randle talked postgame with Walt Frazier about what led him to this season’s approach, particularly cutting down on the threes and upping his attempts from in close: “It’s just me recognizing my size, my strength, my quickness, my [footwork] – all that is an advantage,” Randle said. “ . . . when I went back this summer and looked at my game, looked at the tape, I was like ‘I’m able to get wherever I want to on the court as long as I’m patient, and just playing the right way’ . . . I feel I can get to the rim at will, especially with the guys I’m playing with as the floor opens up.” Behold:

Randle’s holding the ball less and being quicker with it. Potential energy has gone cuckoo for kinetic in 2024, and along with all that faster acting comes faster decision-making. More of these quick brutalities, please.

Randle is not without context, worth remembering when considering any player, or human at all. In 2021 he finished in a virtual tie with Reggie Bullock for the team lead in threes made and attempted. Last year he was first. This year he’s fifth. Water can flow or it can crash. The team around him is so much better. Them being better lets him focus on areas he can be better for this better team. Better for water to stop crashing where it’s limited and instead flow where it flows best.

One pleasant development around the Knicks in the Leon Rose/Tom Thibodeau years is that players who come here continue to develop. Often that kind of player stands out; it’s not every day you can point to one player after another on a roster and boast about their leveling up. Randle continues to tinker, to streamline, to sharpen. Mitchell Robinson has, too. Ditto Isaiah Hartenstein. Immanuel Quickley, when he was here. Jalen Brunson. Quentin Grimes, apparently. I’m not saying any of those players worked harder because of Randle’s example. Awful nice, though, that the most individually accomplished Knick happens to be one who continually tinkers, streamlines and sharpens his game. Can’t be bad for the culture.

During the 2021 season, in a piece for the Players’ Tribune, Randle wrote:

“I don’t think I realized everything that goes into being a #1 option in the NBA . . . It means the other team’s defense is dialed in with an actual game-plan to stop you . . . there’s pressure on you, every play, to figure out how to get to your spot on the court . . . if you don’t execute like you’re supposed to, it’s not just a bad individual night — it’s probably a loss . . . I was supposed to be one of our leaders . . . help establish what our identity was as a group . . . set an example of what it took to be a winning player . . . who could not only play at a high level, but . . . raise the level of those around him. As much as the team needed my scoring . . . they might have needed my leadership even more. And I didn’t give it to them.”

As far as regular season impact, you might already be able to put Randle’s resume above Carmelo Anthony’s, as far as Knick years. The Knicks appear to be on track for a third year out of four finishing 10+ games over .500, something they haven’t done since P.J. Brown was public enemy #1. But Randle, the Knicks and their fans are all looking for signs that this postseason will be different – for him and for them. Water takes the form of whatever container its in; it becomes all that is possible. If Randle can do the same, the Knicks may become all that they’ve been aiming for, too.