Truth of fact, truth of feeling: Julius Randle, Karl-Anthony Towns & the newest New York Knicks

Meet the new hope. He’s a lot like the old hope.

“Our language has two words for what in your language is called ‘true,’” Jijingi says in Ted Chiang’s “The Truth of Fact, The Truth of Feeling.” “There is what’s right, mimi, and what’s precise, vough. In a dispute the principals say what they consider right; they speak mimi. The witnesses, however, are sworn to say precisely what happened; they speak vough.”

The Knicks acquired* Karl-Anthony Towns from the Minnesota Timberwolves for Julius Randle, Donte DiVincenzo and a protected Pistons’ 1st-round pick as likely to ever convey as Trump is to concede in November. The asterisk means the deal ain’t fin; our brave new CBA requires the Knicks move another nearly $9 million off the books or else the terrorists win. What about the bits we can see? What assumptions were exposed after a deal that, despite being rumored for months, still threw so many for a loop?

One queer Knick continuity continues with this trade: no great Knick ever retires happily as a Knick. Expand the definition of “great” all you like, the line holds. Carmelo Anthony was practically shoved out of town. Amar’e Stoudemire did the ceremonial nonsense where a player signs for a day with his old club to retire there, but after the Knicks waived him in 2015 STAT played another 75 games combined for Dallas and Miami; him retiring as a Knick is like Jesus ascending unto heaven, only to stop on the way to do some consulting work for Allah and Joseph Smith, then reaching the pearly gates expecting to be remembered for Golgotha.

Patrick Ewing preferred a year in Seattle to a farewell tour with New York, and New Yorkers didn’t exactly march on LaGuardia to protest his flight outta town. Bernard King was let go as much for the knee injury that ended his glory days as the independence he showed rehabbing it; the greatest Knick of the Holtzman/Riley interregnum retired a New Jersey Net. Micheal Ray Richardson was already dealing with a contract dispute and suspensions for missing flights and games by the time he was traded for King. Walt Frazier spent his last three seasons with the Cavaliers. Willis Reed did retire as a Knick, after one too many devastating knee injuries and his teammates only voting him half a playoff share.

Even the primordial Knicks were cursed. The Korean War couldn’t keep Carl Braun apart from the Knicks, but he spent his last year with the Celtics. Harry Gallatin’s goodbye came as a Piston, as did Dick McGuire’s. Richie Guerin retired a St. Louis Hawk, and when he came out of retirement to play again he did so with the Atlanta Hawks.

For Randle, there is symmetry to his New York story, something rarely afforded Knick greats, and while he won’t end up on the Mount Rushmore of Knicks fans who saw the Golden and Silver Ages last century if there’s a pantheon for the best ‘bockers this century, Randle enjoys a position of prominence among them. You can bookend his Knick career with injuries to 7-footers: he became a Knick after the Kevin Durant free agency dream died once KD tore his Achilles in the 2019 Finals, and with Mitchell Robinson continuing to Marcus Camby before our very eyes, one season after another pockmarked by injury, the Knicks traded Randle from a position of some strength to buttress another with none.

I’ve never seen a Knick dismissed as many times as Randle was turn out as great as he has.

First he was the Durant booby prize, the Knicks’ shame incarnate: big, yes, and gifted for his size, but of course nowhere near as tall or gifted or cool as KD; a freight train driving to the rim, sure, but not the bigger bullet train in that year’s draft, Zion Williamson. After Randle’s first year with the Knicks, one so frustrating that by its end even Mike Breen couldn’t hide his exasperation with the spin-into-traffic turnovers, most fans were ready to dump him for a first-round pick, any first, the same yield the team turned for Marcus Morris. The next year he was incredible in the regular-season, but stumbled badly in the playoffs against Atlanta; as those playoffs coincided with the return of live crowds, Randle’s poor play led some to suggest his issues were between the ears, rather than the inevitable outcome of a cute 40+ win team with a dearth of creative offensive players being exposed the way 40+ win teams with a dearth of creative offensive players often are.

A year later Randle’s shooting cooled while some other bits overheated, evident in pissiness towards coaches and teammates and giving the fans a taste of their own medicine. In 2023 he put together another great campaign but hurt his ankle near the end of the season; despite returning early from the injury, re-injuring it late in the opening round versus Cleveland before returning again in the next against Miami, his struggles struck some as more of the same. Last year Randle was playing as well as he ever had in New York before separating his shoulder in January, in what turned out to be his last game as a Knick.

From one mad vantage point, Randle did nothing but fail over five years in New York. And now he’s gone, so if the team does anything but completely collapse the trade is justified. If the Knicks win a title with Towns, or even reach a conference finals or win 60 games, Randle’s the new Walt Bellamy. But to dismiss what might have been happening with Randle here would be to risk missing the forest for one of its trees, or the mimi for the vough.

So much of what we take in from the world around us is pre-determined, practiced and presented with such polish it’s easy to slip into thinking that’s just the way it works, that what we observe is what was intended. It wasn’t. Most live music has been practiced hundreds if not thousands of times, and anything recorded, in addition to the manipulative magic of production values to dress it up even more. Much of what you read on this here internet has been edited, re-edited and re-re-edited before it ever reaches the twinkle in your eye (and yet despite this, there is a dearth of editors). Your favorite shows, films and video games go through a million scripts before shooting even starts, after which there’s even more revision.

Does knowing that have any effect on the things you love?

Maybe Randle couldn’t handle 10-15 minutes a night playing center. Maybe his limitations were plain as day to those with clearer eyes, minds and hearts than mine. Maybe he was lefty Carlos Boozer. But maybe Randle was a story. A story that wasn’t ready after the first draft, or the second, or the third, the fourth, the fifth . . . but that was getting there. Maybe all it needed was a little time. A little faith. Maybe we all do. Arrivederci, St. Julius, the non-believers’ patron saint of the unbelieved-in.

Karl-Anthony Towns is the Earl Monroe Chris Paul was supposed to be. Pearl was a finishing piece when the Knicks acquired him from Baltimore in 1971-72, a title contender transferring a significant-enough talent to its bottom line to put them over the top, and it did: New York lost in Finals that year before winning it all the following. That kind of move never happened in the Ewing era. The next time it nearly did almost was 2010, when Paul was supposedly going to be the last domino to fall in place after Stoudemire and Melo. We’ll always have a wedding toast.

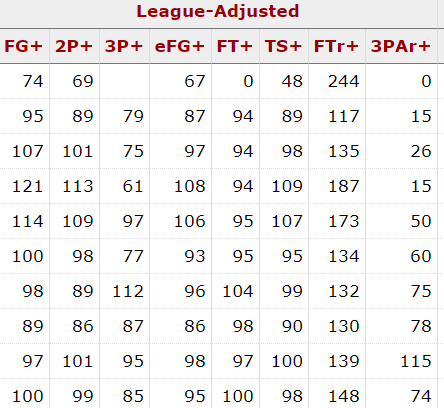

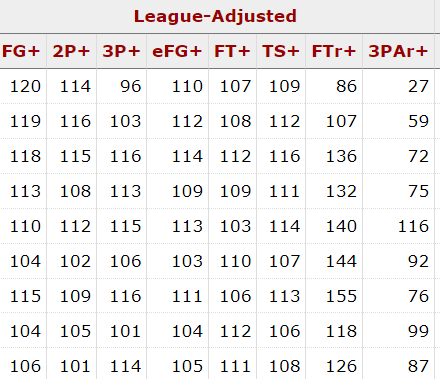

Now Towns is here, a more precise answer to questions asked of Randle, though it remains to be seen whether that answer is right. KAT is bigger, a true 7-footer with the more conventional size, if not skill set, for the center spot than the man he replaces, and a better shooter from pretty much everywhere: at the rim, in the paint, the short midrange, long midrange and beyond the arc. Look at their adjusted shooting numbers. 100 is considered league average; anything over 100 is better, under 100 is worse. These charts cover overall field goal percentage, 2-point, 3-point, free-throw and true shooting percentage, plus free-throw and 3-point rate (how often they attempt free throws and 3s compared to the league average). Randle’s career chart is the first one, followed by Towns’. Don’t get lost in the forest of numbers; just note how often you see triple-digit values in one chart versus the other.

The Knicks’ new sum of all hopes is a man whose prior team knew him for 10 years and decided “Nah.” Then again, the Wolves traded Kevin Garnett when he was 30 and didn’t win another playoff series till he was 48. When they needed a point guard and could have drafted Steph Curry they used consecutive picks on two point guards who weren’t Curry. Soon after that they sent Kevin Love to Cleveland for a package led by Andrew Wiggins and Anthony Bennett. Early talk after the Towns deal sounds like Randle is less meaningful to them for his presence than what his sooner-than-later absence could mean for their cap sheet, and of course Minnesota is famously a free-agent destination. Generally speaking, if the Wolves think they’re moving in the right direction you wanna head the other way. That’s what happens when the fish stinks from the head down.

Minnesota’s general manager, the esteemed Tim Connelly, has an out in his deal in case of an ownership change, where as it turns out there’s a tug of war between Glen Taylor – whose hands have been on or near the wheel for every wrong turn this car-crash of a franchise ever made – and the devil-you-don’t-know, a group headed by Alex Rodriguez – a wife-cheating, drug-cheating, union-betraying pariah despised everywhere he played who’s thrown family as well as teammates and co-workers under the bus rather than admit that a liar lied. “But Anthony Edwards!” you say. How much you wanna bet he’s a Wolf by 2027?

Not long ago the Knicks were a physical, deep team whose continuity was a defining feature. Go back a year, when the only change they’d made all offseason was trading Obi Toppin and signing DiVincenzo. Maybe that wasn’t the vough way to build a champion, but it felt mimi enough to try. Since then, trades and CBA red tape have disappeared RJ Barrett, Immanuel Quickley, Quentin Grimes, Evan Fournier, Malachi Flynn, Ryan Arcidiacono, Bojan Bogdanović, Shake Milton, Mamadi Diakite, DaQuan Jeffries, Isaiah Hartenstein, Randle and DiVincenzo. The return of Towns, OG Anunoby and Mikal Bridges may have made the Knicks better. Does it get them any closer to a parade? It very well may have. Is that the point? It may very well not be.

“The Truth of Fact, The Truth of Feeling” cuts back and forth between two stories: one a modern-day single father navigating his relationship with his college-aged daughter in a world where all memory is instantly recorded, stored and retrievable; the other that of a young Tiv who, in learning writing from a Western missionary, learns something about his people he’d never suspected. The stories center on assumptions exposed after we alter the way we experience our past. Both father and scribe are shocked by what they find – no monster, no ghosts nor villains. The father finds a difficult path to a better relationship with his child; the writer is reminded that people deserve better than the truth.

It took too many Knicks fans too long to recognize that while Randle may not have been their hero, he was no villain. Towns seems to have suffered the same slander in Minnesota. I cannot for the life of me imagine what the future holds for either. My heart is sad, but hope remains, and there are worse reservoirs to pour one’s hoops hopes into than a man who can call himself the greatest shooting big of all-time and not be laughed at. We’ll never know how far the Knicks might have gone with Randle; even if Towns lasts 10 years in New York the same may be true of him, given just how many outside factors factor into any team’s finish. There are truths we can’t know, truths we won’t and the few we’re allowed. Maybe winning it all with Randle or Towns isn’t what matters. Maybe what does is something far better.