Just how good is Mitchell Robinson, and how good can he become? A deep dive

Is Mitchell Robinson the next Rudy Gobert or the next Andre Drummond? Or somewhere in between? Or somewhere lower? Derek Reifer examines the curious case of Mitch, a non-shooting big who’s due for a payday soon, and is also probably the Knicks’ best prospect.

Knicks basketball is back.

It’s been a whirlwind of a month, from the draft to free agency to training camp, and there’s obviously a ton to talk about in the world of Knicks basketball. They have a brand new eighth overall draft pick who hails from New York City, a bunch of fresh free agent faces on good contracts, and a brand new coaching staff from top to bottom. Despite all that, the most common talking point the past week has been this:

Well, not that specific photo, of course (although it is fantastic), but the player. The third-year center known as Mitchell Robinson has been the trending topic, and it’s hard to sift through all of the news and rumors to find what’s legit. He fired his fifth agent — what’s his problem? The Knicks are questioning his commitment? Or maybe they’re really high on him? These days, it really depends on who you ask and where you look.

So why has Mitch been on everyone’s minds, considering everything else going on in training camp? Well, the most obvious point is that Mitch is simply interesting — skipping college, falling to the second round and eventually becoming debatably the best prospect on the Knicks; already showing crazy outlier NBA skills within his first two seasons:

The bigger issue, though, is probably that the Knicks have a huge Mitch decision creeping up on them. He’s in the final guaranteed year of his rookie contract, and although he has a team option for next season for absolute pennies ($1.8 million), there’s a catch — if the Knicks pick up that option, Mitch becomes an unrestricted free agent in 2022, free to go wherever his heart desires. If the Knicks decline the option, he becomes a free agent a year earlier, but will be restricted, and thereby the Knicks would have the right to match any foreign offers for his services.

There was a similar situation in 2018 for the Nuggets, as their young second-round center Nikola Jokic neared the end of his rookie deal, and the Nuggets ended up declining the option to sign him to a massive extension.

Of course, based on what we know now, not even the most optimistic of Knicks fans would consider Mitch to be of Jokic’s caliber yet, so there’s a whole lot of nuance to the upcoming decision, and all of the sudden, 2020-2021 becomes a massive measuring-stick season for the young center. What caliber player is Mitch, and what caliber player will he be in a few years? What’s “Prime Mitch” worth, both on the court and on the contract books?

Well, based on his offseason workout videos, he’s basically Prime Kevin Durant:

We’ve seen enough Hoodie Melo videos at this point, though, to know not to put too much stock in empty-gym workouts. After all, before last season he said he wanted to shoot more threes:

He attempted zero on the year. I think it’s fair to say that the idea of “Prime Mitch” will develop more in the way of incremental improvements on what he currently is as a player than suddenly adding Allen Iverson’s handle and Ray Allen’s jumper.

So what is he currently as a player? For one, he’s clearly the best player — right now — of the Knicks’ young prospects.

Here’s a view, courtesy of BBall Index, of notable Knicks’ value this past season across various catch-all impact metrics, showing Mitch as a clear outlier:

Most people think of his impact from the defensive end first, which makes sense considering defense is generally more important than offense for bigs. He’s been the best in providing defensive value, even more than French Prince of Drip Frank Ntilikina:

It wasn’t just on defense, though, where his performance has stood out. Here’s the same view with the offensive components of the advanced metrics, where he actually stands even further ahead of his teammates:

What exactly can Mitch do on offense to provide such immense value as a non-shooter? The key is in his efficiency — when Mitch touches the ball, it almost always means something great is about to happen. Per Cleaning The Glass, he’s ranked 99th and 100th percentile for his position in points per shot attempt his first two seasons, and doesn’t turn the ball over, either:

It’s a recipe for incredible offensive efficiency. When he gets the rock, more often than not, there won’t be a steal, there won’t be a block… just a bucket.

Of course, we have to strip a good bit of causation away from that correlation. After all, most times he gets the ball, he’s already running down an open lane or skying for a rebound right next to the hoop. There’s obviously a difference between being an efficient finisher and an efficient creator, and although Mitch is an efficient finisher (and that is valuable!), it’s not as valuable as the alternative. We can revisit the above table and note his extremely low percentiles in usage and assist percentage, which further underscore the lack of creation ability.

I know I risk some Knicks fans immediately closing the page when I make this comparison, but look below for a similar view of the first two seasons for another NBA big man:

That’s Andre Drummond’s first and second year in Detroit. Although he wasn’t as crazy efficient as Mitch in points per shot and turnovers, he had much more of an offensive load, as evidenced by his higher usage numbers (and also a little bit less abysmal assist percentage).

In the following seasons, Drummond expanded his offense even more, taking more hook shots and jumpers to the detriment of his — and his team’s — efficiency. This gets back to the common thread of “Prime Mitch” — assuming the offensive game doesn’t really “round out” with good-enough shooting and playmaking, what’s his offensive ceiling and how valuable are those contributions?

Well, in a more literal sense, his “ceiling” is high:

Mitch is an absolute havoc-wreaker on alley-oops. That Portland game was debatably his best game of this past season — he went 11 for 11 on field goals for his best game score of the year. Those 11 field goals:

Putback layup

Layup

Dunk

Alley-oop dunk

Dunk

Alley-oop dunk

Tip layup

Putback layup

Alley-oop dunk

Alley-oop dunk

Tip layup

The shots aren’t exactly coming from a wide variety of places, but to complete 4 alley-oops in a single game is patently insane. Here’s another one from the same game - notice how Frank barely even has to look before tossing this one up:

We basketball nerds talk a lot about gravity (in the sense of pulling defenders close to you) when referencing shooters like Steph Curry running around screens, but gravity exists inside the arc, too. I’m not the first to coin the term, but Mitch has a sort of vertical gravity — when he’s getting these alley-oops so easily, teams are forced to overcommit, and this makes things easier on other players. It’s a way of thinking about playmaking without the ball, and if Mitch can improve significantly on what’s already an elite finishing package, it would lend optimism to him becoming a real positive cog contributing to a championship-level offense.

Thanks to awesome data work by Andrew Patton, we can actually visualize Mitch’s gravity on opposing defenses relative to the median NBA player:

Now that’s a lot of gravity in one place. Almost enough to even puncture spacetime as we know it….

I’m aware that was corny, but humor me.

When talking about gravity, though, what’s more important? Having a ton of pull in one direction or having a little less pull in many different directions?

Sure, Mitch doesn’t hit threes, but perhaps even more important is the fact that he doesn’t even shoot them. He’s absolutely no threat from anywhere outside the paint — and this can make things difficult. When the conditions are just right, it’s great to be a specialist. But in a changing environment, it’s better to be a generalist. When teams can game plan specifically to a player’s strengths and weaknesses — like in an NBA playoff series — they can mitigate the impact of a specialist’s, well, specialty. We haven’t seen Mitch in an NBA playoff environment just yet, but there is cause to concern if Prime Mitch is just a one-trick pony on offense, no matter how incredible that trick happens to be.

Let’s look at the gravity chart for a former Knick big man as a comparison:

Note that although nowhere does Portis’ gravity get anywhere near to the -12 Mitch had near the rim, he’s a threat around the whole court. Of course, I’m in no way saying Bobby Portis is a better offensive player than Mitch (to speak nothing of his defense), but this information is worth noting. It’s especially notable within the context of the fact that the Knicks’ best two-man (Frank Ntilikina and Bobby Portis), three-man (Kevin Knox, Ntilikina, and Portis), and four-man (Damyean Dotson, Knox, Ntilikina, and Portis) lineups by net rating last season all included Portis, with no sign of Mitch. And net rating includes defense!

Thinking back to the context of the Knicks needing to make a decision on Mitch’s contract, let’s look at the top six centers in the NBA in 2020 by salary per Spotrac:

Of course, salary value doesn’t necessarily reflect real value on the court, but it does provide insight on what kinds of resources teams are willing to allocate to one player. Looking down the list, all of those centers can either shoot threes well, play-make for their teammates at a high level, or both — right up until Rudy Gobert, who happens to be a two-time NBA Defensive Player of the Year. We can’t speculate too much on what a Mitch extension might look like, but it’s safe to say that for him to turn into a real max-money type star, he’s going to need either tangible improvements in his weaknesses or be best-in-the-league at his strengths.

Let’s take a separate look at one of those strengths, though — defense:

Again per Cleaning the Glass, Mitch’s cream-of-the-crop finishing ability is joined by a cream-of-the-crop shot blocking ability; over 96th percentile in both of his seasons. He’s also done an incredible job at racking up steals for a center, and looks like he’s well on track to be an elite offensive rebounder (fgOR%). His biggest issues have been fouls (though he showed marginal improvement in year 2) and, somewhat shockingly, defensive rebounding (where he actually regressed in his second year).

Trigger warning for another Andre Drummond comparison:

This is reminiscent of the similarities we saw in the offensive profiles. Andre was almost as good at the rim, but was significantly better at both rebounding and not fouling.

However, to me, these stand out as Mitch’s best potential opportunities for future growth. It’s hard to see how much better he can get at blocking shots or dunking, and to go from zero 3-point attempts over two whole seasons to a marksman would be nearly impossible. However, defensive rebounding, for one — especially when Mitch is already really good at offensive rebounding — seems like a logical focus area for growth.

I think the fouling is fixable, too. He’s actually shown the ability to improve upon his fouling over the course of the season — in both his rookie and sophomore years there was a general downward trend in his fouls per 100 possessions. I charted this below:

What’s strange is that the progress he seemed to make over the course of 2018-19 didn’t stick at the beginning of 2019-20 — he had to make those same improvements all over again. I don’t want to buy into all of the “commitment” hoopla that the media has thrown around regarding Mitch, but something like that might put a tiny doubt in the back of your mind.

And, of course, correlation doesn’t imply causation. However you slice data, you might be able to find a different trend. Here’s the same fouling metric, but by number of days off before the game:

Interesting — it could be that when he’s less rested, Mitch makes more lazy fouls, and vice versa. Regardless, the numbers seem to show the fouling is something Mitch does have the ability to improve upon — and with everyone singing the praises of the Knicks’ new development staff, this should be another immediate focus for tangible improvement.

So, assuming he can make strides on fouling and defensive rebounding, what’s Mitch look like on defense?

In my opinion, the complete package.

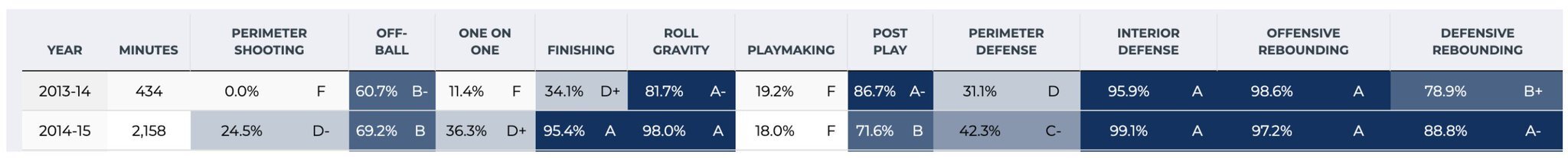

Per BBall Index, here are Mitch’s data-driven play type grades over his first two years:

These follow along pretty closely with what we saw in the Cleaning the Glass percentiles, but with one key standout — perimeter defense.

Although he regressed in 2020 (a more-common-than-it-should-be theme), his perimeter defense has graded out as close to excellent both seasons, which has the potential to be a real differentiator for him defensively.

Here’s Andre Drummond again:

Although Drummond showed a high steal rate, he didn’t grade nearly as well in perimeter defense overall — part of what makes Drummond attackable defensively.

Now, here’s that two-time Defensive Player of the Year I touched on earlier, Rudy Gobert:

Again, significantly better rebounding, but poor perimeter defense. This is debatably the number one reason Rudy Gobert has been “exposed” in the playoffs — inability to adapt; specialist instead of generalist, but this time defensively. Teams have been able to game plan to get Rudy in the right situations and almost play him off the court — that’s what separates 82-game players from 16-game players, as Draymond Green likes to say.

Speaking of Draymond Green:

Now, Draymond is of course a different archetype than Mitch, especially offensively. But he’s a Defensive Player of the Year whose game has clearly translated to the postseason. Mitch graded out as as-good-or-better than Draymond in both interior and perimeter defense, in both seasons! Again, that pesky defensive rebounding desperately needs to improve, but Mitch’s potential to be a jack-of-all-trades on defense — while already being an elite rim protector — gives him a legitimate path to DPOY potential.

Taking a look at the film gives a broader idea of both how much Mitch is able to do on defense and why Tom Thibodeau is such an intriguing option as a coach to bring it out of him. First off, his normal old help defense at the rim is consistently good:

Even when stationed at the rim, his recovery ability to the 3-point line — part of that tantalizing perimeter defense ability — is damn near superhuman. He’s actually pretty clearly the best in the league at blocking threes, via Ian Levy:

It’s a fantastic ability to have, not only for the obvious reasons of defending the three — and perimeter in general — being valuable, but these blocks can actually turn into good transition opportunities as well:

It’s also important to view his defense in the context of pick-and-roll. With the Knicks, he’s commonly been employed in a “drop” scheme, where he essentially sits back to roam in the paint regardless of the screen’s success. This obviously utilizes his elite shot-blocking well — the defense can concede the usually-inefficient midranger, and leave Mitch to suffocate the drive to the rim, sometimes even recovering after the block to affect the ricochet 3-pointer!

Here he holds strong to again cut off the drive, but the guard passes to try to take advantage — Mitch absolutely swallows this Cody Zeller “attempt”:

Tom Thibodeau, though, made himself famous in his time with the Bulls utilizing an “ice” defensive scheme. This is different from drop coverage; instead of sitting back, the big aggressively pushes up onto the dribbler to force them sideline:

This type of strategy has fallen out of favor a bit in recent years, as leaving the roller (who can more and more often hurt you from the outside) is a tough sell. However, it might be interesting to see how Thibs employs Mitch this way — it’s a system that should allow him to expand upon his perimeter defense skills, giving him more possessions face-to-face with a guard with some distance away from the basket. Thibs utilized a mobile defensive anchor in Chicago, and Joakim Noah won Defensive Player of the Year doing exactly this:

Mitch has in his toolbox so much of what you’d want in a young prospect — some already-elite skills, and a couple of places for realistic improvement. Using Kostya Medvedovsky’s predictive advanced metric DARKO, we can compare Mitch’s trajectory to that of other young centers. Bam Adebayo is an interesting blueprint — showed potential early, got a good team around him, had a coming out party in the playoffs, and eventually earned a massive extension from his draft team. Mitch is pacing ahead of Bam here:

Do note, however, the tapering off of the red curve about two-thirds through. The question about Mitch isn’t “is he good” (he is); the question is how good can he realistically get? What are his tangible paths to improvement? We’ve seen many cases throughout this piece where he was unable to improve, or sometimes even regressed, like in year 2. In order for these DARKO progressions to hold as much optimism as many of us want them to, Mitch needs to show us these tangible improvements — and soon, especially considering his contract situation.

Now that I have the qualifiers out of the way, why not drink in some more optimism:

In many ways, it’s unfortunate that after so many poor seasons, the Knicks’ best prospect happens to be a non-shooting big. But in so many other ways, it’s fascinating — New York just made massive investments into development staff the same season that Mitch has a de facto contract year; the same season that Mitch is hearing rumors fly about his attitude and commitment. There’s an undoubtable range of possible outcomes, including further regression, or even (gasp) turning into the next Andre Drummond. But there’s also a legitimate path to Defensive Player of the Year, and the kind of building block every developing team craves. As a Knicks fan, but also a basketball fan, I can’t wait to see what this season has in store.